“The Machine Stops” ‒ E. M. Forster’s short story today

In his short story “The Machine Stops” (1909), E.M. Forster (1879–1970), renowned as the author of subtle social novels such as “Howards End” or “Room with a View”, sketches a disconcerting scenario of a future – one that nonetheless comes across as almost familiar to us today.

A Guest Contribution by Professor Dr Stefan Willer

(Associate Director of the Zentrum für Literatur- und Kulturforschung (ZfL)

at Humboldt-Universtität zu Berlin)

In his short story “The Machine Stops” (1909), E.M. Forster (1879–1970), renowned as the author of subtle social novels such as “Howards End” or “Room with a View”, sketches a disconcerting scenario of a future – one that nonetheless comes across as almost familiar to us today. This applies, in particular, to the eponymous “Machine”, an all- encompassing communication system, by which Forster seems to anticipate the Internet. People devote themselves entirely to the virtual exchange of, and mutual commentary on, “ideas”, without ever having to speak directly to one another. The system also provides for food, clothing and medical care.

Vashti, one of the protagonists of the story, lives as a hairless and toothless “lump of flesh” isolated in an underground room, just like all her peers, and delivers lectures on music during the “Australian period” to interested listeners. Vashti’s son Kuno, by contrast, refuses to let himself be pacified by the Machine. He begins to ask and act; he seeks out experiences that are no longer envisaged in his world, and he wants to tell his mother about them in person. Forster’s short story deals, not least, with the challenge posed by a direct conversational and narrative situation. The very first sentence places us, as readers, exactly in such a situation: “Imagine, if you can, a small room, hexagonal in shape, like the cell of a bee.” In this way, the narrator leads us into Vashti’s dwelling, while making us realise how remote we are from that world. The distance between the narrative present, which is repeatedly emphasised, and the remote future cannot be bridged by any time machine, but only by imagination itself.

Though Forster’s vision of the “Machine” is nothing less than remarkable, he does not actually foresee a specific technological development here, but rather tries to set himself apart from his own present day around 1900 by striking out, so to speak, the futuristic emphasis inherent in the latter. Perhaps this is why this short story means so much more to us today – we who live in a world full of technology and instruments, in which, however, narratives of progress hardly seem to play a role. What happens if, one day, in a world without a sense of history, the system stops working? Can humankind, which has already shut itself down completely, find a new way of existing or will it perish together with the Machine?

On 1 and 2 June, “The Machine Stops” by E.M. Forster will be performed at the Futurium as part of a lecture performance. The performance is a joint work by Johanna Wokalek and Fabian Russ.

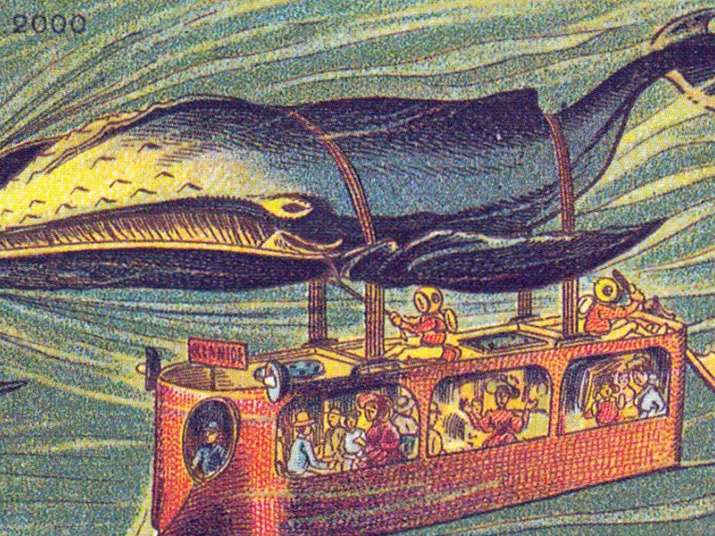

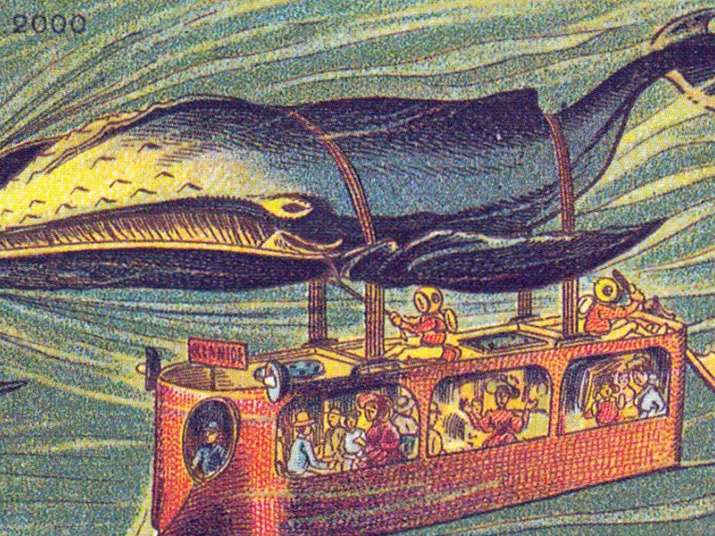

Picture: By Jean Marc Cote [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons