The Whale Bells project brings the sound of whales to the surface

Message from the Depths of the Oceans

The warm, muted sounds of the Whale Bells are both art object and message: a message from the past, from long-extinct rorqual whales to their descendants today, the humpback whales. “A part of the whales’ ears that once perceived sounds now creates sounds,” Jenny Kendler explains, referring to the bells’ clappers, which stem from the ear bone of a whale species from the Miocene Epoch. This is how it sounds:

Artist and activist Jenny Kendler created Whale Bells in collaboration with Andrew Bearnot. It all started with the ancient ear bone: “We got the fossils from a diver who found them in coastal rivers near Beaufort in South Carolina,” Bearnot says. Because such bones are covered in lots of sediment underwater, they are found mainly by feeling around. “A really compelling act to imagine.”

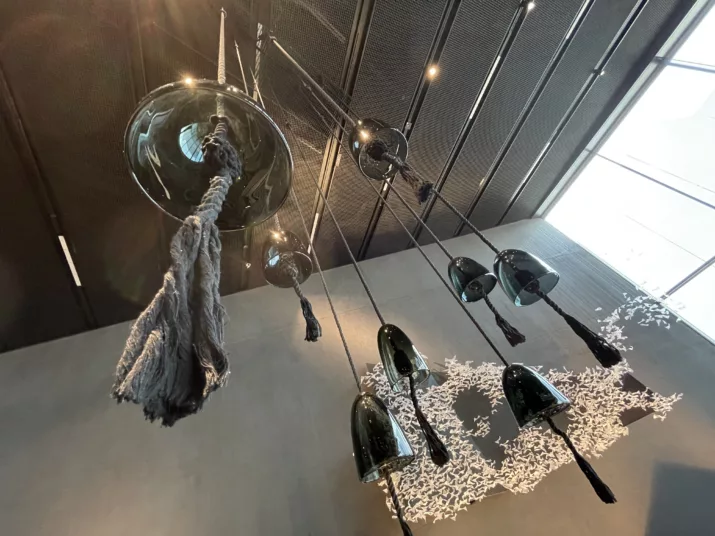

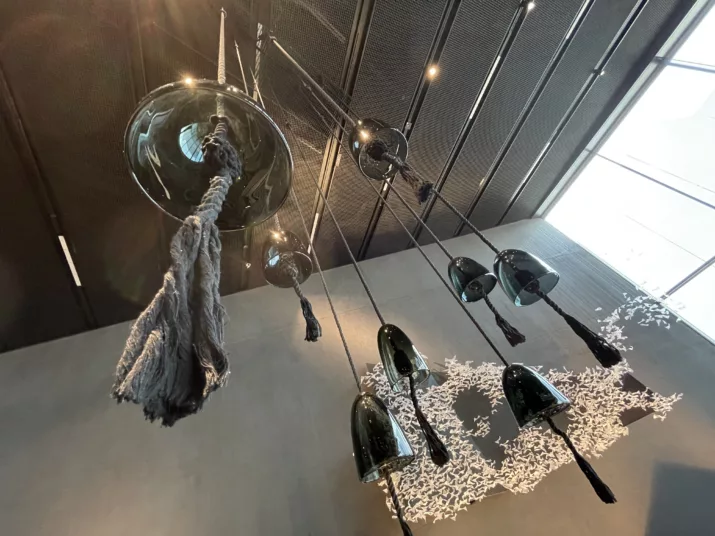

Eight Whale Bells are on display in Futurium’s Thinking Space Nature. They symbolise the conflict that arises from human intervention in nature: “Millions of years ago, whales sang and communicated throughout their pristine seas, long before humankind began to pollute the ocean with the noise of human activity,” Kendler says.

Jenny Kendler and Andrew Bearnot with the Whale Bells.

Photo: David Sampson

The two artists are fascinated by whale communication. “The songs of whales are complex, and we still know so little about them,” Bearnot says. For the artist, whale communication is a language and, at the same time, an art form. “Or something in between.” According to Bearnot, it is a sign that the concept of human exceptionalism is not tenable, because the latter is based on the belief that humans are the only species that has language or creates art.

Melancholic and mysterious

“What could be more melancholy, beautiful and mysterious than the song of whales in the depths of the sea?” Jenny Kendler asks. In her view, we should understand it as a message urging us to stop exploiting the earth. “Although whale hunting has become less common, it’s still practised in Norway, Iceland and Japan. Many whale species also suffer from noise pollution in the oceans.”

And that is something that should not be underestimated: industrial shipping, seismic exploitation of oil and gas deposits, as well as naval sonar, can disrupt whale communication and, in some cases, even lead to the death of the animals. For example, if they surface too quickly in order to escape the noise and, as a result, bleed to death. According to Kendler, this fact still receives far too little attention.

Strange interaction between whales, oil and climate change

Whale Bellswants to change that: the ombré tones – that is, tones that shade into each other – of the hand-blown glass bells are meant to evoke the depths of the oceans, while the ropes and knotwork are reminiscent of nautical techniques. “When a sailor dies at sea, a bell is tolled eight times to signal the end of the watch,” Kendler explains. The bells are also symbolic of the strange interaction between whales, oil and climate change: “Whales were hunted to extinction because of their so-called blubber, the animals’ tran, which was used as oil for lamps and as machine lubrication during the early days of industrialisation,” Andrew Bearnot says.

With the industrial production of oil, the hunting of whales decreased. “The whales were saved by industry, so to speak.” But only at first glance, because today the industrial noise pollution caused by the extraction of oil and gas in the depths of the seas presents an acute threat to the whales.

Kendler says: “We hope to move the viewers of Whale Bells to think in new ways about our relations to these mysterious ‘others’ and to their habitat.”